Our company was growing fast. Too fast, it turned out, for our monolithic dbt project. The marketing team had their definition of a customer, based on leads from their ad platforms. The product team had theirs, based on application sign-ups. The finance team had a third, based on billing records.

In one quarterly meeting, all three presented a different “total number of customers.” It wasn’t just embarrassing; it was a symptom of a deeper problem.

Our attempts to democratize data had led to anarchy.

We needed a system that provided both freedom and responsibility. We needed a way for the central data team to provide a solid foundation while still allowing domain teams to move quickly.

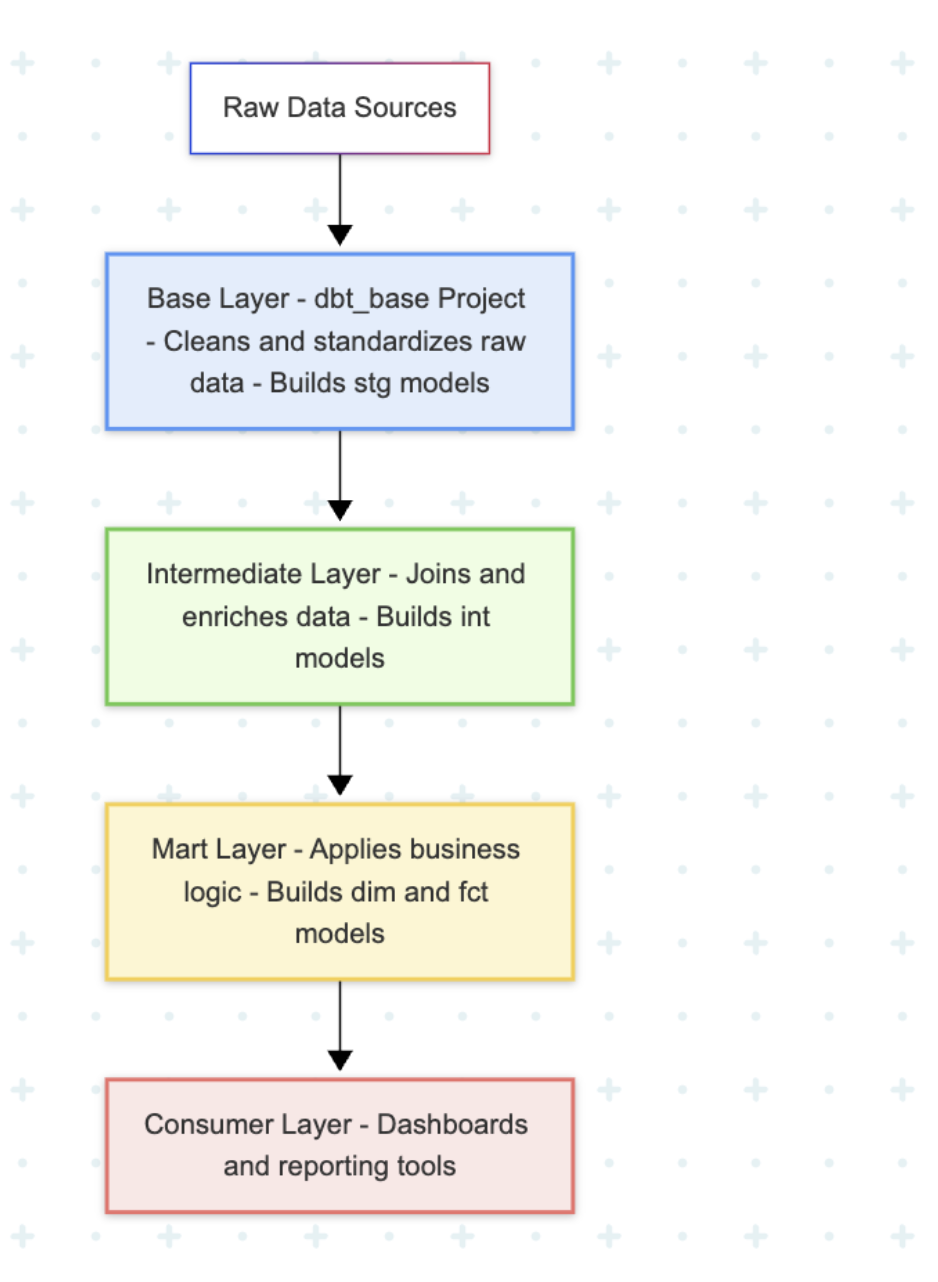

The “dbt Layer Cake” wasn’t a top-down mandate; it was the peace treaty we designed to stop the chaos.

The first layer is the base project, owned by the central data platform team. This is our sanctum sanctorum.

It connects to the raw, messy source data and produces one thing: clean, tested, trustworthy, foundational models.

This is where the one, true dim_customers model lives, with all its gnarly logic for deduplication and identity resolution.

The other teams—Marketing, Supply Chain, etc.—now have their own dbt projects. But their projects are forbidden from touching raw data. Instead, their packages.yml file must import our dbt_base project as a dependency.

When a marketing analyst needs customer data, they don’t write their own logic; they just call ref(‘dim_customers’). They get to build their own complex marketing_funnel models, joining our trusted customer table with their ad-spend data, but they inherit our definition of “customer.”

This federated approach stopped the arguments and rebuilt trust in the data.

The domain teams got the agility they craved, and the central team could finally guarantee that everyone in the company was speaking the same language.

The Architecture That Ended the Civil War: